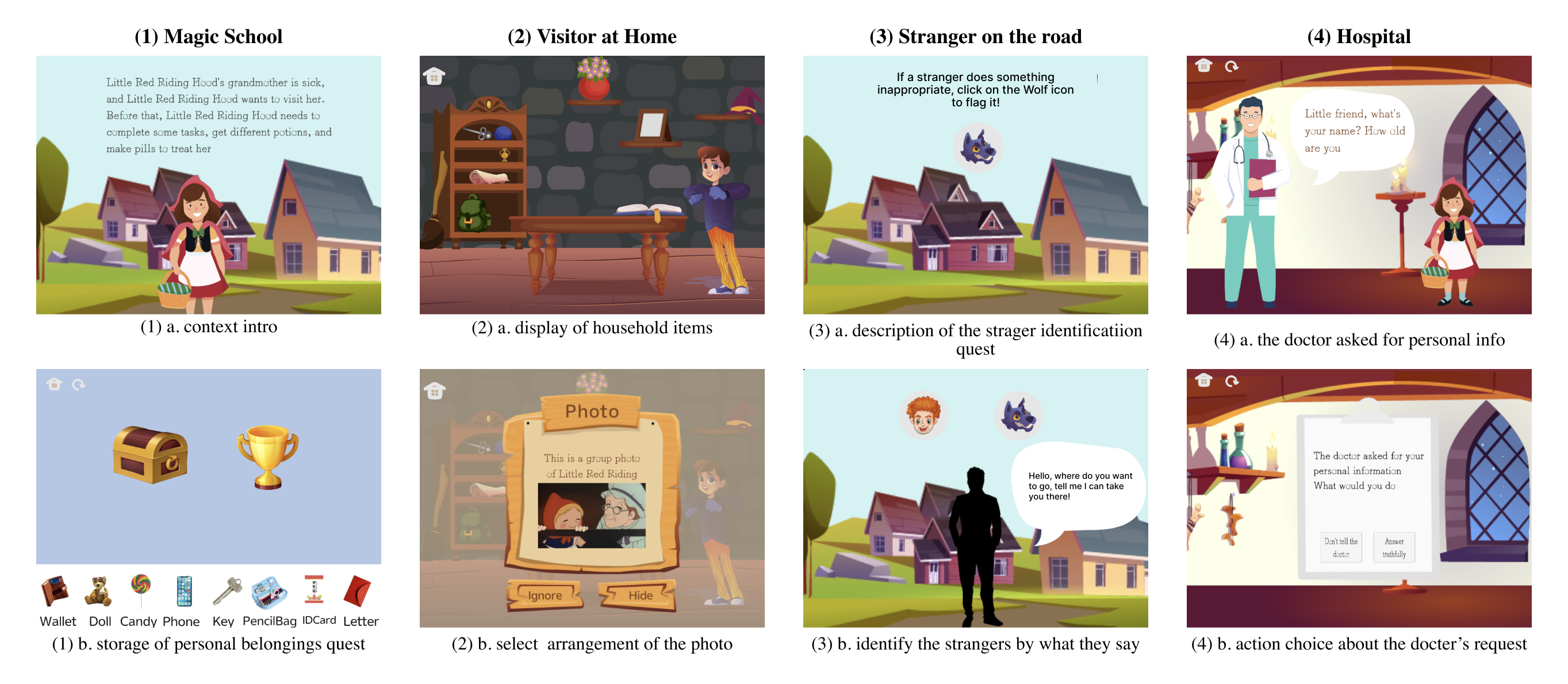

Game Design

We had three objectives in designing this privacy education game. We want to teach them to: (1) understand the concept of personally identifiable information and personal belongings; (2) recognize privacy norms in different social contexts; (3) respond to privacy threats appropriately. We integrated two types of privacy concepts into our game: personal information and physical privacy. In each of our game scenes, players interact with different populations in different contexts: showing personal belongings to the staff at schools; putting away personal items at home when strangers drop by; responding to strangers’ questions in public; responding to a doctor’s requests in a hospital.