Method

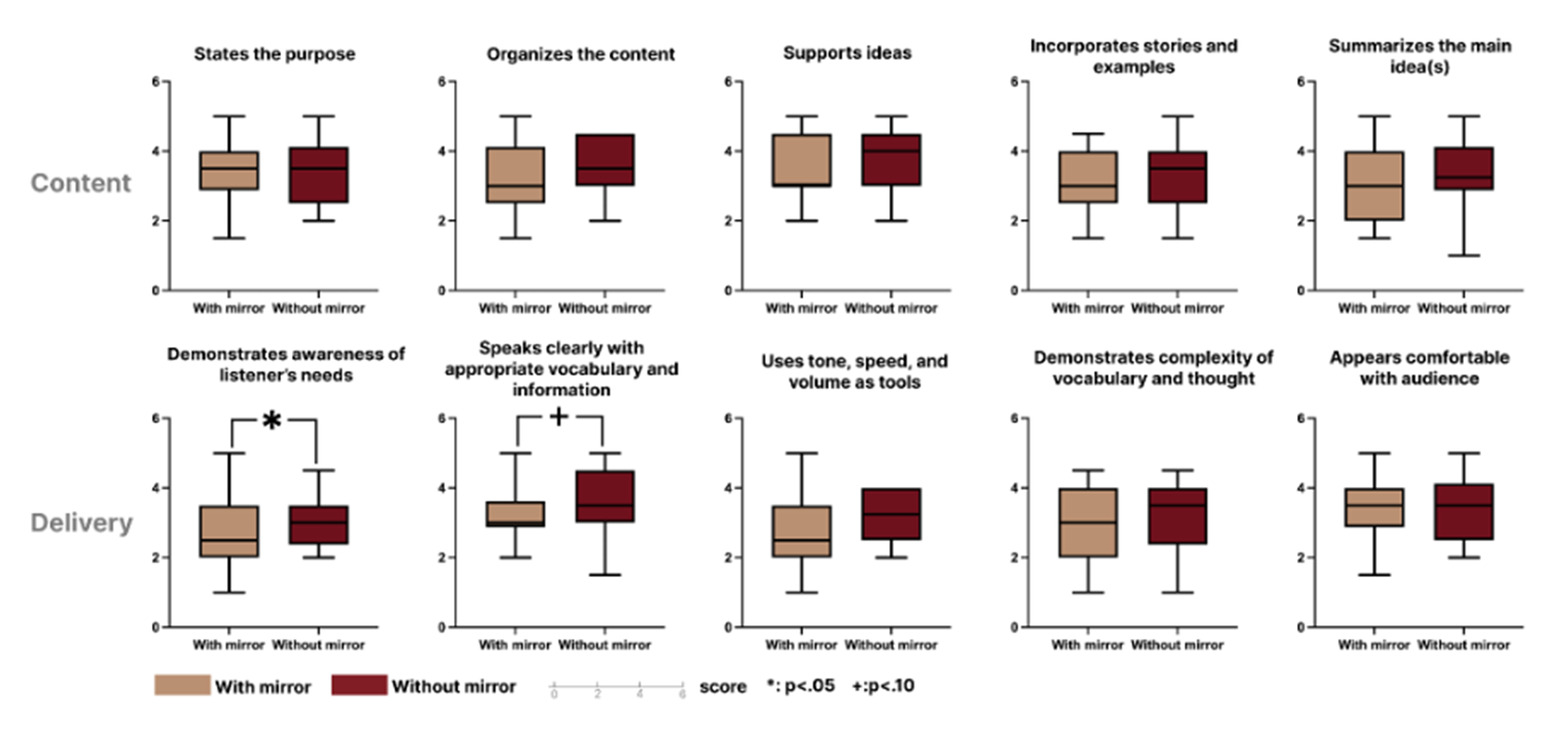

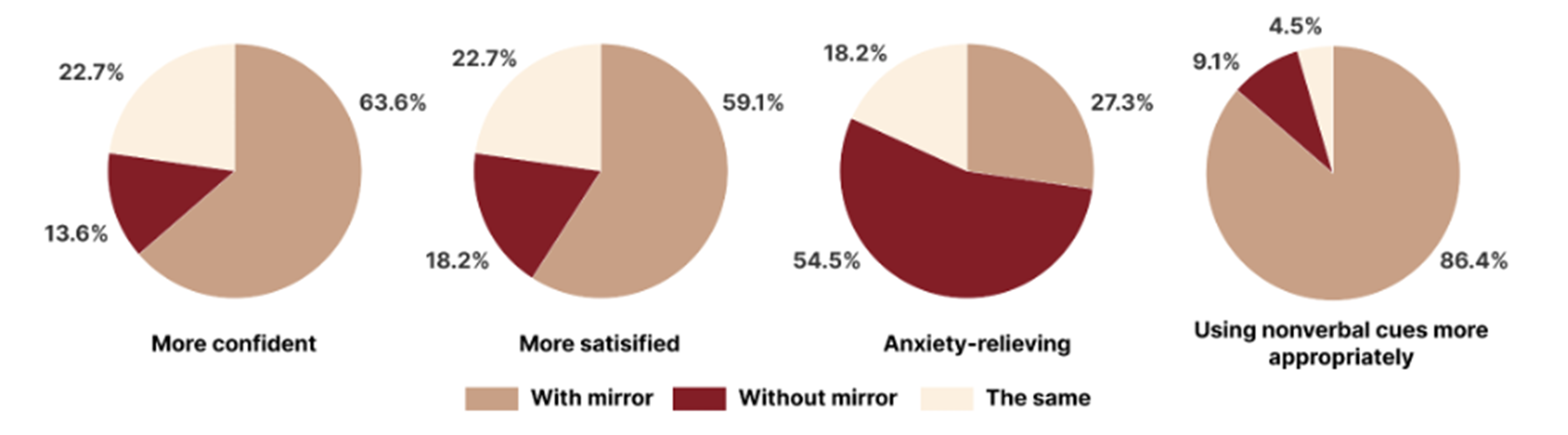

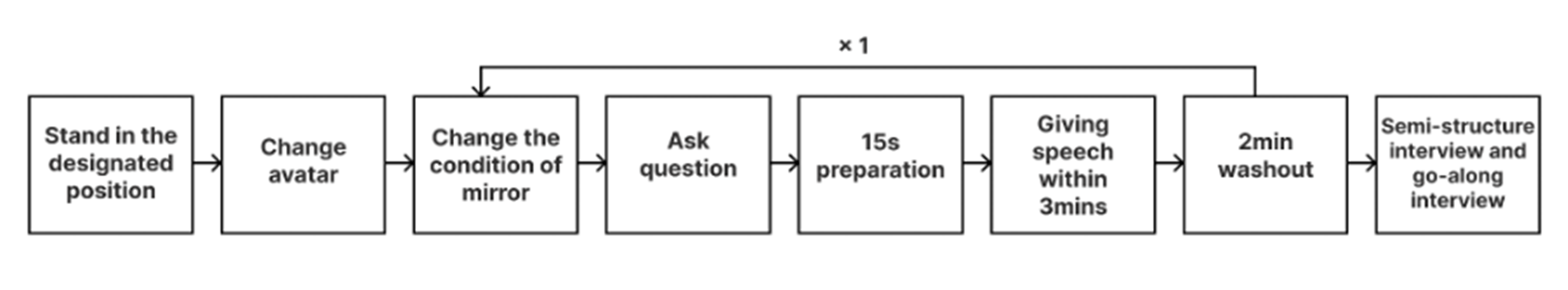

We conducted in-depth interviews to explore user perceptions of mirrors in social VR, addressing RQ1. As communication mainly occurs through conversation, we investigated RQ2 by examining the influence of mirrors on interpersonal communication. To answer RQ2, we conducted a controlled experiment with conversational tasks (speaking performance) in mirror and non-mirror settings using a VR headset. Follow-up interviews were conducted, and performance was evaluated using the Public Speaking Competence Rubric scored by external scorers.

Mixed method experiment workflow

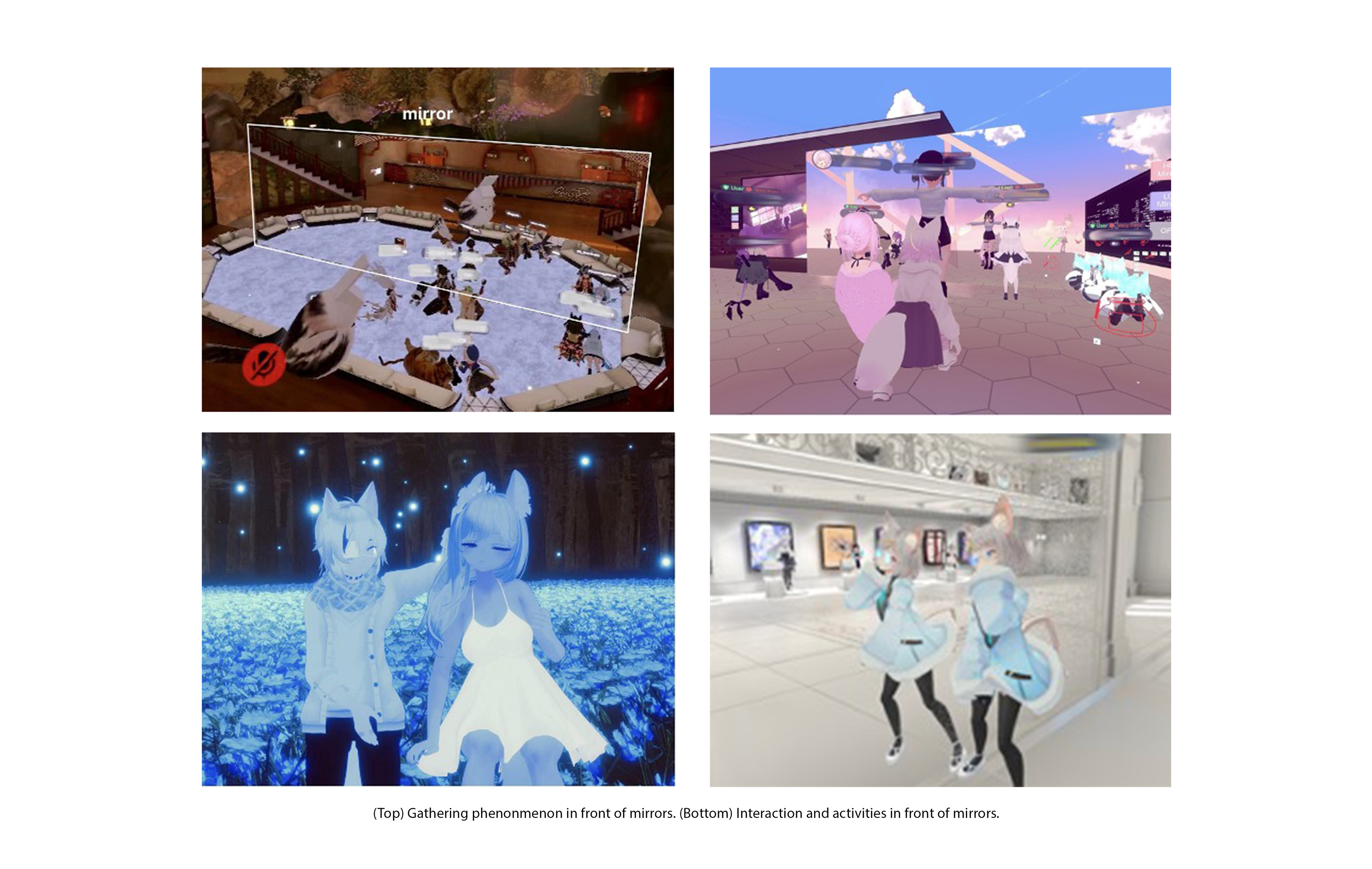

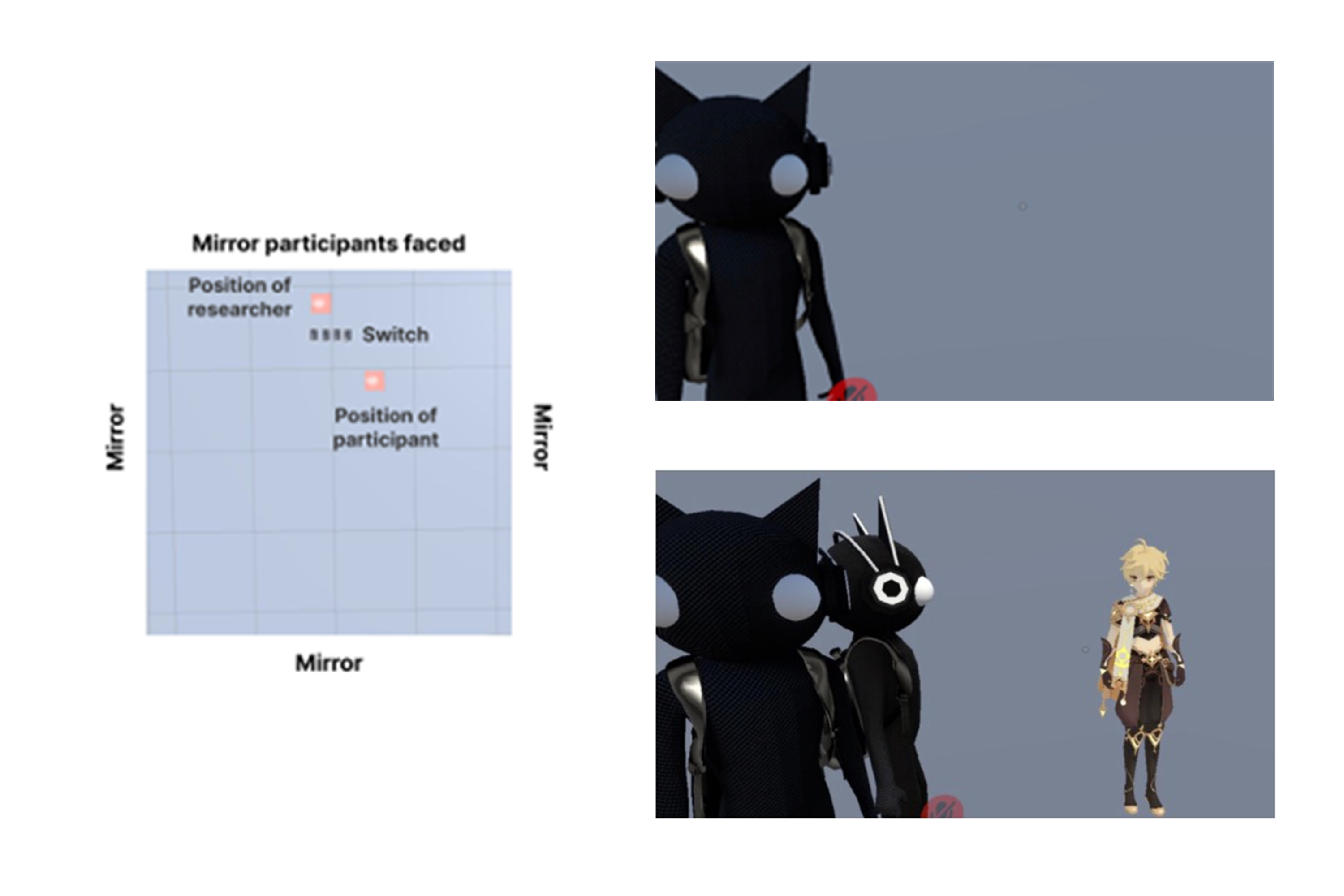

Overhead view of the pre-designed experimental and mirror on/off from participants’ view