Method

We conducted a multi-phase qualitative study, including observations of practical NPI practices and semi-structured interviews with 16 NPI practitioners (11 therapists and 5 caregivers). Therapist here refers to the trained professional who provides therapeutic interventions or treatments to PwDs, and caregiver refers to the professional care provider, who provides care and assistance to PwDs. During our study, we didn’t specify what kinds of technologies our participants have used so that our fndings could be open to technologies with various levels in our targeted technology-mediated NPI practices.

Obervation

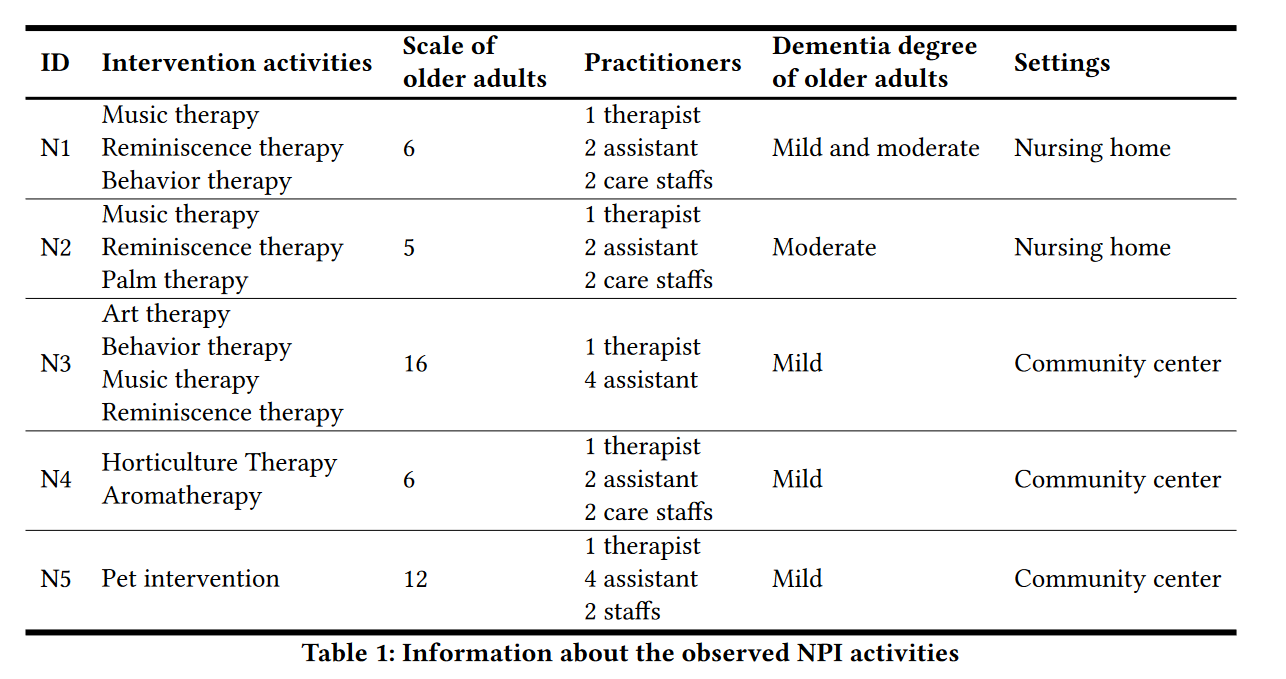

We began with the observations of in-person NPI activities, with the purpose of obtaining frsthand insights into NPI practices for PwDs in real-world NPI scenarios.Table 1 shows details of the observed fve activities. The duration of each activity was approximately 40 minutes.

Semi-structured Interviews

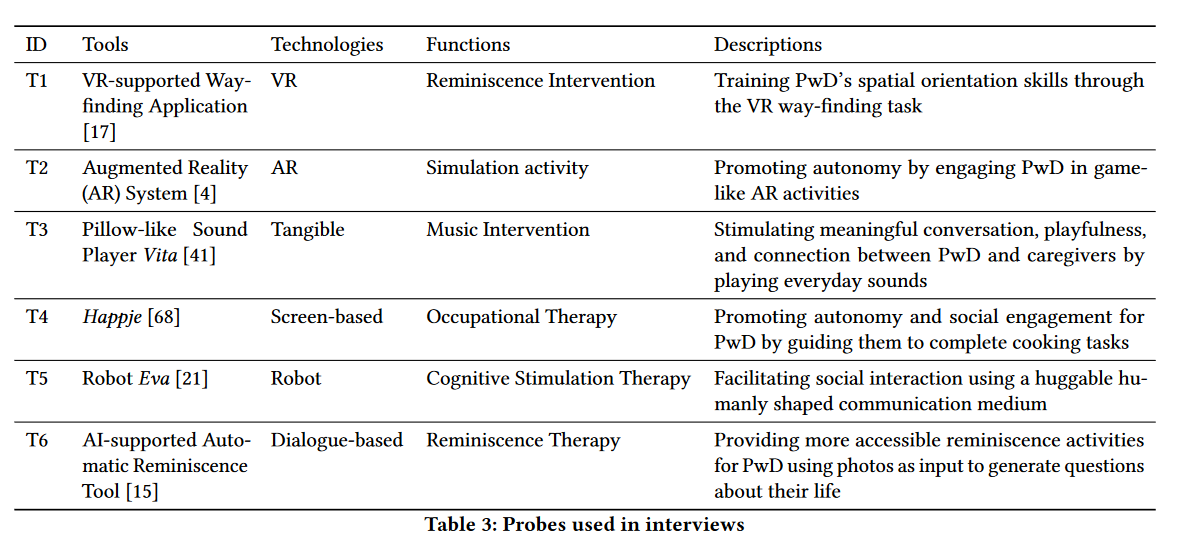

To deeply understand NPI practitioners’ practical experiences of using technologies to support NPIs, and their attitudes, perceptions and expectations of technology-mediated NPI, we then conducted semi-structured interviews with 16 NPI practitioners (11 therapists and 5 caregivers). The probes used in interview were listed in Table 3.